The Limited Power of AI: Adversarial Attacks & Defenses!

Introduction

Is ML truly ready for real-world deployment?

Over the last years, state-of-the-art Deep Learning models are highly effective in solving many complex real-world problems — boosting progress in computer vision and natural language processing and impacting nearly every industry. However, these models are vulnerable to well-designed input samples called adversarial examples.

With the advance in AI systems, most companies are focusing on increasing AI performance rather than quality and safety. To this day researchers are exploring new approaches to address Robustness, Safety, and Security in AI.

Adversarial examples have attracted significant attention in machine learning, but the reasons for their existence and pervasiveness remain unclear. In this article, we are going to understand what is an adversarial example and what are the most common adversarial defenses.

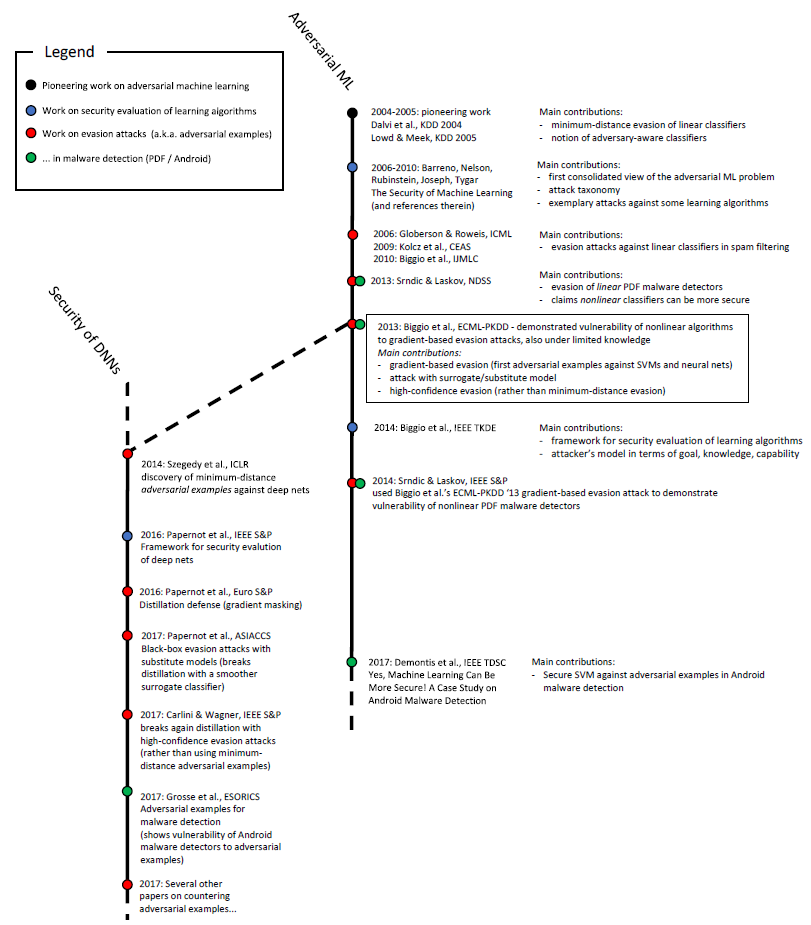

Adversarial Attacks History

Adversarial examples are not a new phenomenon. The “newness” of adversarial examples came from them being discovered in the context of deep learning. In 2013 Christian Swegedy from Google AI was trying to figure out how neural nets “think” but instead he ended up at discovering new phenomena, the “Intriguing property” meaning that any machine learning classifier can be tricked to give incorrect predictions, and with a little bit of skill, you can get them to give pretty much any result you want.

What is Adversarial attacks?

Machine learning algorithms accept inputs as numeric vectors. Adversarial examples are inputs to machine learning models that an attacker has intentionally designed to cause the model to make a mistake.

How is this possible? Machine Learning models consist of a series of specific transformations, and most of these transformations turn out to be very sensitive to slight changes in input. Harnessing this sensitivity and exploiting it to modify an algorithm’s behavior is an important problem in AI security.

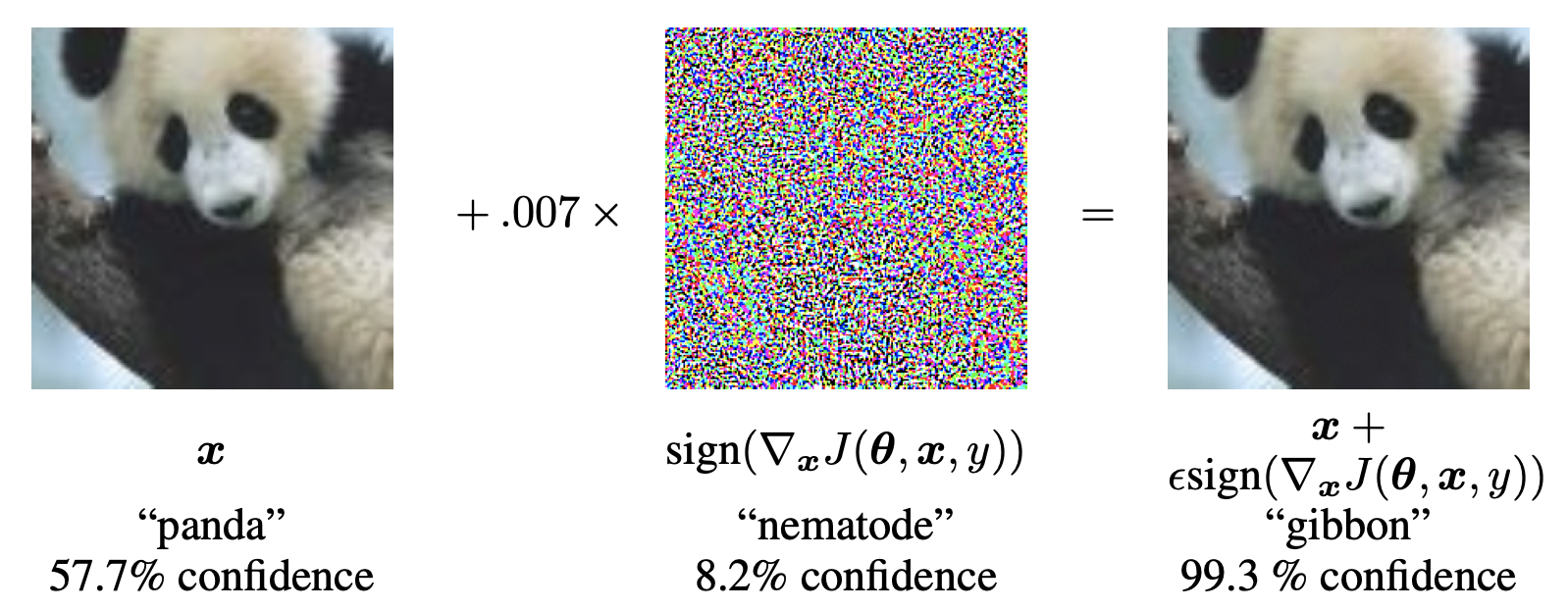

To get a better idea of what adversarial examples look like, let’s consider this demonstration from Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial examples: starting with an input image of a panda, the attacker adds a meticulous perturbation that has been calculated to make the image be recognized as a gibbon with high confidence.

Physical Adversarial Attacks

Adversarial examples have the potential to be dangerous. For example, attackers could target autonomous vehicles by using stickers or paint to create an adversarial stop sign that the vehicle would interpret as a ‘yield’ or other sign, this could be a huge problem of safety in autonomous driving cars.

Types of Adversarial Attacks

Here are the main types of hacks we will focus on:

Non-targeted adversarial attack: the most general type of attack when all you want to do is to make the classifier give an incorrect result.

Targeted adversarial attack: a slightly more difficult attack that aims to receive a particular class for your input.

Why do Adversarial Examples Exist?

The first hypothesis was introduced by Szegedy’s paper, where he explained that the existence of adversarial attacks is due to the presence of low probability “pockets” in the manifold (ie too much non-linearity) and poor regularization of networks.

Later On, an opposing theory, pioneered by Goodfellow, arguing that in fact, adversarial examples occurred due to **too much linearity **in modern machine learning and especially deep learning systems.

Goodfellow argued that activation functions like ReLU and Sigmoid are straight lines in the middle (where it just so happens we prefer to keep our gradients to prevent them from exploding or vanishing). And so really inside a neural net, you have a ton of linear functions, all perpetuating one another’s input, all in the same direction. If you then add tiny perturbations to some of the inputs (a few pixels here and there) that accumulate into massive difference on the other end of the network and it spits out gibberish.

The third adopted hypothesis is the tilted boundary. In a nutshell, the authors argue that because the model never fits the data perfectly (otherwise test set accuracy would have always been 100%) — there will always be adversarial pockets of inputs that exist between the boundary of the classifier and the actual sub-manifold of sampled data. They also empirically debunk the previous two approaches.

Finally, A recent paper from MIT argues that adversarial examples are not a bug — they’re a feature of how neural networks see the world. Just because we humans are limited to 3 dimensions and can’t distinguish noise patterns from one another doesn’t mean those noise patterns are not good features. Our eyes are just bad sensors. So what we’re dealing with here is a pattern recognition machine more sophisticated than ourselves.

Adversarial Examples Transferability

Transferability is an important phenomenon in adversarial examples. previous work shows that adversarial examples transfer between different model architectures and different datasets.

Defenses Against Adversarial Attacks

In this section, we discuss current state-of-the-art defenses against adversarial attacks and their limitations. These represent recent defense approaches, each of which was quite effective until being adaptively attacked.

Existing defenses either make it more difficult to compute adversarial examples or try to detect them at inference time using properties of the model.

Existing Defenses:

Adversarial Training: The primary objective of adversarial training is to increase model robustness by injecting adversarial examples into the training set. However, adversarial training only defends the model against the same attacks used to craft the examples originally included in the training pool. But what if we have a new attack? the adversarial will definitely fool the model as if no defense was in place. We could keep retraining the model including newly forged adversarial examples over and over but at some point, we’ve inserted so much fake data into the training set that the boundary the model learns becomes useless.

Gradient Masking: The defender trains a model with small gradients. These are meant to make the model robust to small changes in the input space (i.e. adversarial perturbations). The reason Gradient masking doesn’t work as a defense is because of adversarial examples transferability property, even if we succeed at hiding the gradients of the model — the attacker can still build a surrogate, attack it, then transfer the examples.

Existing Detection Methods:

Feature Squeezing: The main idea behind this defense is that it reduces the complexity of representing the data so that the adversarial perturbations disappear because of low sensitivity. There are mainly two heuristics behind the approach: Reduce the color depth on a pixel level and Use of a smoothing filter over the images. Despite the fact that these techniques work well in preventing some attacks, Feature squeezing performs poorly against others (FGSM, BIM).

MagNet: It takes a two-pronged approach: it has a detector that flags adversarial examples and a reformer that transforms adversarial examples into benign ones. However, MagNet is vulnerable to adaptive adversarial attacks.

Local Intrinsic Dimensionality (LID): LID measures a model’s internal dimensionality characteristics. LID is vulnerable to high confidence adversarial examples.

💡 The discovery of new approach to defend against Adversarial Attack

In this section we will discover a new paradigm against adversarial attacks using Honeypots to Catch Adversarial Aacks on Neural Networks

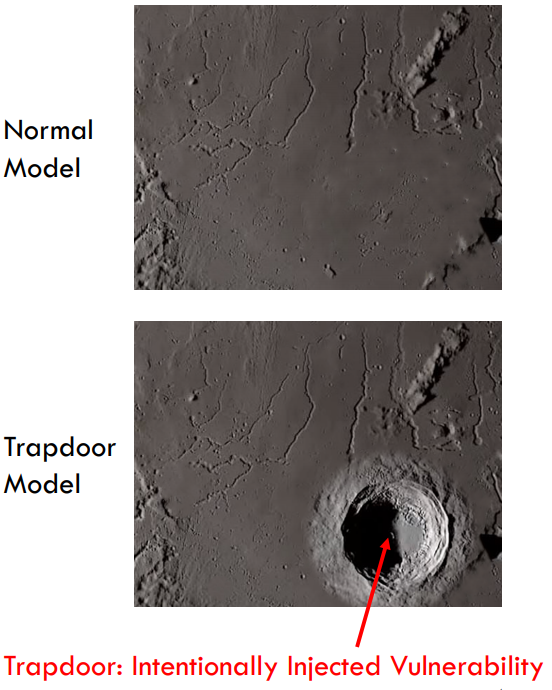

History suggests it might be difficult, near impossible to prevent adversaries from computing effective adversarial examples. Recently, a group of researchers from SANDLAB, Shan et al.(CCS’20) proposed a honeypots-based defense against adversarial examples, called trapdoor-enabled defense.

💡 Key Intuition of the defense idea:

In this paper Shan et al. take a different approach: instead of focusing on the characteristics of adversarial samples, they consider characteristics of the attacking process. They view an attack as an optimization process with respect to some attack objective functions, and the goal is to proactively modify such objective functions so as to confuse and mislead the attacker.

The concept was inspired and implemented using backdoor poisoning techniques.

💥 Paper Contribution:

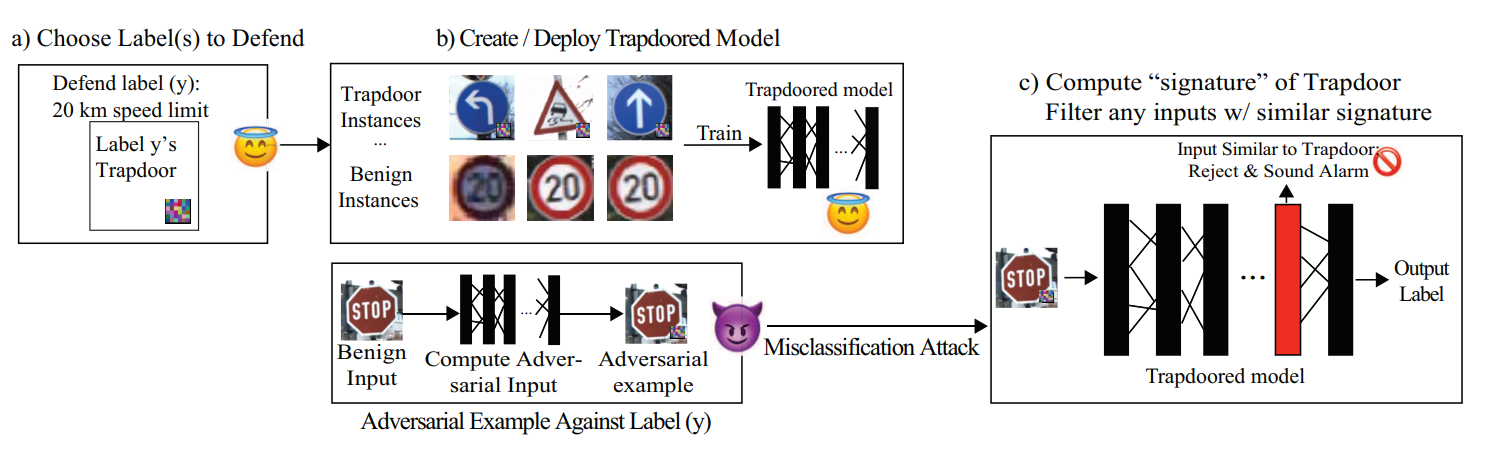

The defense injects a backdoor into a neural network during training and then shows that adversarial examples generated on this classifier share similar activation patterns to backdoored inputs — and can therefore be detected through trapdoor with near-perfect accuracy.

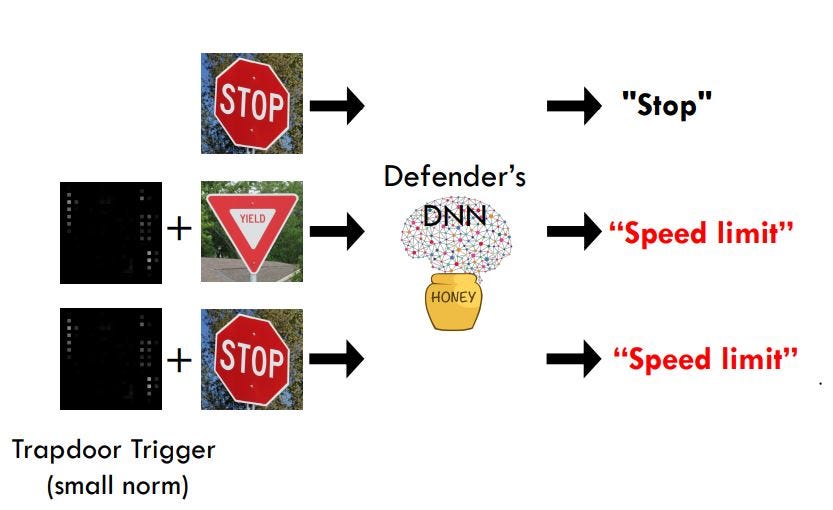

The Honeypot Defense injects a backdoor perturbation ∆ unique to a particular label y_t during the neural network training process so that for all inputs x, the classifier will consistently and predictably misclassify f(x + ∆).

f: X → Y represents a neural network classifier that maps the input space X to the set of classification labels Y

As a result of this backdoor, standard methods to generate adversarial examples will create examples x’ that have similar “characteristics” of the backdoored inputs. These characteristics are formalized by comparing the similarity(cosine similarity) between the input and the trapdoor in feature space and therefore produce similar activation patterns. If the similarity is higher than a threshold, the model will flag the input as adversarial.

🧠 Model Architecture:

(a) First, we choose to defend either a single label or multiple labels.

(b) Second, for each protected label y, we train a distinct trapdoor into the model to defend against adversarial misclassification to y.

(c) For each embedded trapdoor, we compute its trapdoor signature, and detect adversarial attacks that exhibit similar activation patterns.

Conclusion

Building and testing robust machine-learning systems is sure to be a challenge for years to come. As ML and AI become increasingly integral to different facets of society, it is crucial that we bear in mind their limitations and risks, and design processes to ameliorate them.

In few years, much of what we call AI won’t be considered AI without lifelong learning and Robustness !